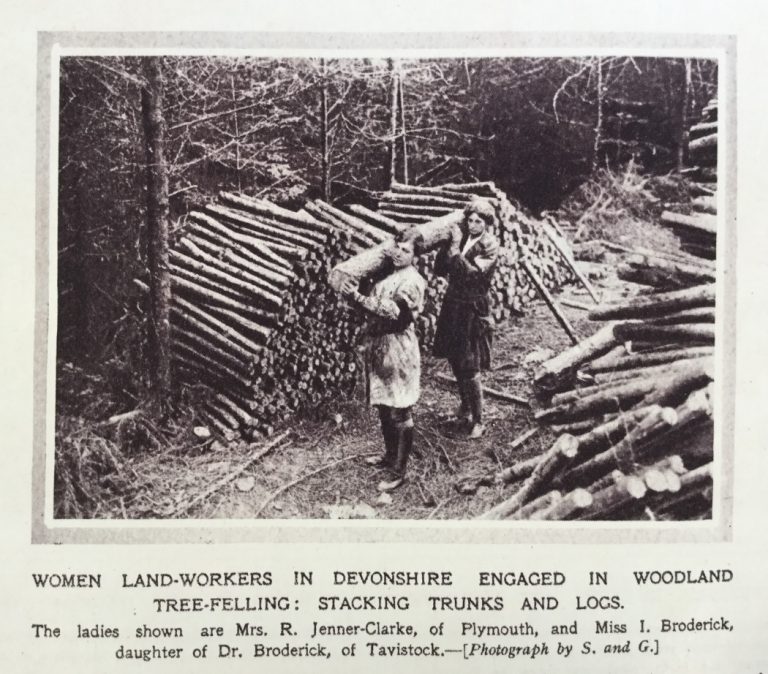

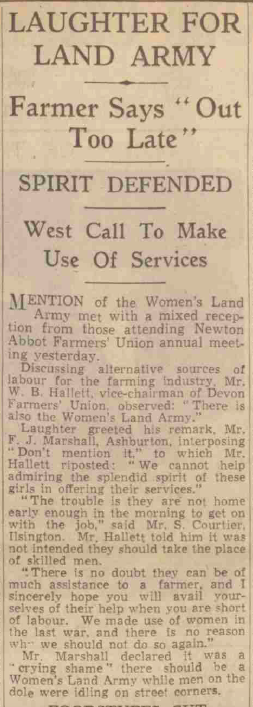

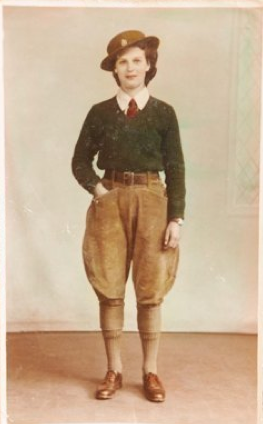

BILLETED TO DEVON

Despite what you may imagine, the Land Girls were usually young women who had been billeted in from cities all over the UK. They would sign up for the WLA under the understanding that they would need to leave home, and in most cases this was seen as a form of evacuation with a means of getting them out of areas in danger of bombing. Girls from rural areas were less likely to be accepted into the Land Army or Timber Corps as they were already based in a place considered to be safe and where they were likely to be working on their family farms. This led to some division between the local village girls or farmers’ wives and daughters and the WLA members who had often come from grammar school education or work as a secretary in a town or city.

Private farms would take on a member of the Women’s Land Army to help them with their general labour, and farms all over Dartmoor and Devon would have had one, sometimes two, young women staying with them.

In most cases, only one girl would be at a farm at a time and so it could be a lonely existence, particularly on some of Devon’s most rural farms. Often too, the local girls would see the Land Girls as snobbish or promiscuous and they would be treated unfairly if they went into the villages.